[Note: This post contains spoilers. It expands on my original review of Silence, which appeared at St. Louis Magazine on January 11, 2017. Updates 2/1/17.]

One of the telltale marks of a great religious film is that it can move even the faithless. Any work about spiritual matters is clearly doing something right when it resonates with viewers who normally don’t have much use for the adjective “spiritual.” The brilliance of Joel and Ethan Coen’s black comedy A Serious Man, for example, lies in how its droll approach to misfortune entices viewers to adopt the protagonist’s theistic worldview and wrestle with the insoluble problem of evil. Martin Scorsese’s masterful new feature, Silence, is another such film. Its captivating character is an especially striking achievement, given that it is such a relentlessly bleak work, and that its plot deals with the finer points of a moral transgression—apostasy—that by definition has no significance for the godless. Silence is at bottom, a film about uncertainty. It is a work that positively chatters with propositions, suppositions, stipulations, and prevarications—and questions, endless questions. The title signifies not just a mute deity, but the void that humanity fills with its own cacophony of ideas.

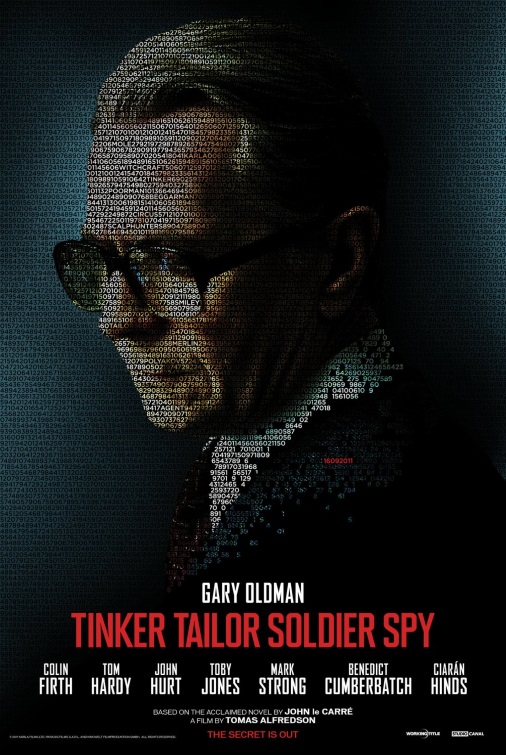

The film’s events take place in mid-17th-century Japan, a time when the Tokugawa shogunate, fed up with Spanish and Portuguese mischief perpetrated under the veil of missionary work, successfully trampled the formally thriving Japanese Christendom into to a quailing, secretive remnant. In all the world, Japan is arguably the state most hostile, both officially and de facto, to the spread of Christianity. It is into this repressive realm that Portuguese Jesuit priests Father Sebastião Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Francisco Garupe (Adam Driver) are determined to venture. Their primary objective is to learn the fate of their former mentor, Father Cristóvão Ferreira (Liam Neeson), who is rumored to have fallen into the clutches of the shogunate and apostatized under pain of torture. Rodrigues and Garupe are sanguine about both Ferreira’s fate and the opportunity to minister to a subjugated community of Christians, but their superior (Ciarán Hinds) has a far more pessimistic view of their prospects, declaring that they will be the last Jesuit missionaries he ever sends to Japan. The viewer has reason to be skeptical as well, given that the film’s prologue depicts Japanese soldiers methodically scalding a visibly broken Ferreira and his allies with sprinkles of caustic, boiling water from a volcanic spring.

The bulk of Silence is divisible into two phases. In the first, Rodrigues and Garupe travel to Japan’s southernmost islands and bear witness to the appalling plight of the nation’s few remaining Kirishitan, as Japanese histories have dubbed these early Catholic converts. In the second, Rodrigues is captured by the local metsuke, a sort of internal security official, and subjected to horrible physical and psychological torments intended to compel him to deny Christ. That’s pretty much the extent of the plot, and although Scorsese gives some scenes the tone of a white-knuckle tale of suspense and survival, the fact remains that much of Silence consists of a heck of a lot of waiting and talking. Moreover, the film’s conversations are frequently long, circular arguments about theology and morality, between parties with differing native languages. Even for a historical drama about Jesuit missionaries, this is solemn, unhurried stuff.

That gravity turns out to be exactly why Silence is so effective at its primary ambition: creating an earnest rumination on conscience, grounded in a theistic framework and given weight by the bloody tangibility of its characters’ situation. The film is decisively a story about Rodrigues and his faith. The principal role of the other characters within the context of that story is to present opposing viewpoints and examples. This is not to say that those characters are thinly drawn or lack agency. For example, the metsuke, Inoue Masashige (Issey Ogata), whom the Jesuits call “the Inquisitor,” is the closest thing Rodrigues has a nemesis. The screenplay by Scorsese and Jay Cocks take pains to ensure that the viewer understands the rationale for Inoue’s pogroms, as well as his frustration with Rodrigues’ obstinacy, without ever losing sight of the metsuke’s unforgiving cruelty. In the end, however, Silence is not about whether Rodriguez wins and Ioune loses, or vice-versa, or about whether they achieve some kind of accord. The film is foremost concerned with the conflict that rages in Rodrigues’ heart, and specifically with the question as to whether he should choose apostasy or death.

(While the lisping, hobbling Inoue is perhaps the most exaggerated figure in the film, he is also one of the few characters based on a historical person, and a fascinating one to boot. The real Inoue Masashige was a high-ranking Tokugawa official who was apparently quasi-open about his homosexuality. He is thought to have perhaps parlayed a romantic relationship with the shogun into advantageous connections and a prosperous civil service career.)

Building a feature around a man’s spiritual tribulations is not new territory for Scorsese, of course. One of the director’s most renowned early films, Mean Streets, is a gritty little crime drama about small-time hoods, shot through with a potent, jittery atmosphere of tragedy. Underneath the film’s genre elements and gratifyingly lean plot, however, lies the deeper tale of ambitious bagman Charlie’s (Harvey Keitel) struggle to reconcile his criminal life with his Catholic faith, and in particular to discern how God wants him to express his devotion.

The more obvious direct antecedent to Silence, however, is the strange, haunting The Last Temptation of Christ, a film unfortunately plagued by a grueling production and blinkered denouncements from the prelates of the Culture Wars. The work itself, however, is an endlessly fascinating imagining of Jesus of Nazareth’s (Willem Dafoe) struggle to acknowledge his identity and fulfill God’s will in the world, even when that will seems obscure or monstrous. Like Scorsese’s latest, Last Temptation is a film suffused with agony, both physical and spiritual, with the former often giving sweat-slicked, trembling expression to the latter. Dafoe’s wild, intensely physical performance portrays Jesus as a man whose seems perpetually on the verge of erupting, bodily: from guilt, panic, rage, and sheer frustration.

However, Last Temptation unfolds in a reality where the supernatural is, if mysterious, at least palpably present. Ghastly omens appear, Lazarus rises from the dead, and Satan visits in the form of a talking serpent, lion, and pillar of fire. Silence has no such miracles. The film’s sole heavenly vision occurs when Rodrigues sees his own reflection in a puddle transform into Christ’s visage, echoing a painting that has engrossed him since childhood. (Notably, that painting is El Greco’s The Veil of St. Veronica, a work that depicts the saint displaying the cloth that blotted Jesus’ face on the way to the crucifixion, capturing a miraculous impression of the Messiah’s face. Rodrigues’ personal visual conception of the divine is therefore an image of an image, underlining his seeming separation from God.) In the context of the rest of the film, this vision is easily characterized as a hunger- and exhaustion-induced hallucination, but it’s no coincidence that this also feels one of the few missteps that Scorsese makes. Most conspicuously, it diminishes the uncanny impact when Rodrigues later hears (or imagines) Christ’s gentle voice at the threshold of his inevitable apostasy.

The dissimilarity between the designs of the two films is also instructive. The Last Temptation unfolds primarily in a a dusty, desolate hinterland, its sunbaked landscapes all sand and craggy stone. It feels almost post-human, in the manner of El Topo. Yet the film simmers with an unmistakable atmosphere of Near Eastern mysticism, owing in part to its grubby, subdued approach to the miraculous, and in part to Peter Gabriel’s landmark score, which fuses electronic and traditional sounds to creates an expectant, almost ritual mood. No such heightened sensibility clings to Silence, which presents a historical “wretched realism” that contrasts with Last Temptation’s magical realism. Scorsese has created ambitious, scrupulously designed historical dramas before—most saliently The Age of Innocence, Kundun, and Gangs of New York—but none of those prior works has the same shambolic, effortlessly authentic look that Silence exhibits.

The Japan that Silence depicts is one of elegant wooden architecture and stunning natural loveliness: pounding ocean surf, gray-green subtropical forests, and impossibly dense white mists. (In reality, the film was shot in Taiwan.) However, it is also a land of starvation, pestilence, and massacre. Silence is simultaneously enamored with its setting’s beauty and yet resolved to portray that setting in all its grimy, feudal awfulness. One of the first images in the film sets the tone. Within a profuse curtain of fog, a dim silhouette emerges, which gradually resolves into a humanoid figure standing sentry near a pair of mounted, severed heads.

The world that Rodrigues and Garupe enter is a grim one, to put it mildly. Echoing recent films as diverse as The Revenant and Hard to Be a God, Scorsese’s film is thoroughly filthy, coated in a slathering of sweat, dirt, shit, blood, and God knows what else. The malnourished, perpetually terrified Japanese peasants dwell in tiny, leaky huts of mud and thatch. Local samurai lords and government officials roam the countryside like merciless devils, taking what they please and meting out rewards and penalties as needed. This includes inflicting collective punishments on entire villages, intended to goad the weak-willed into informing on fellow lawbreakers. In one faintly surreal sequence, Rodrigues returns to a hamlet that he recently visited, only to find the settlement now a ghost town populated solely by hordes of stray cats.

Silence’s vivid portrayal of the violence and oppression in 17th-century Japan has a deeper significance than historical verisimilitude. The misery of the Japanese commoners’ existence is shocking to Rodrigues and Garupe. Portugal itself might be a hearty purveyor of violence and oppression—see: Brazil, Colonization of—but the Jesuits in Silence seem to have no personal frame of reference for the level of repression that the Kirishitan face. Rodrigues and Garupe are the clerics of a majority, state-endorsed religion, and beneficiaries of the comparative stability afforded by early modern Europe’s absolute monarchies and burgeoning mercantilism. They have never had any need for whispered prayers and hidden crucifixes. Their faith has been, in a word, an easy faith, soft and untested.

Observing the forbidding everyday realities of Japanese Christendom firsthand, the Jesuits are confronted with a problem beyond the logistical challenge of ministering to the faithful in secrecy. Their dilemma is also spiritual. On the one hand, they are awestruck at the endurance of the Kirishitan’s faith in the face of subjugation. The fire that the priests see in the souls of their newfound flock fortifies their own resolve and missionary zeal. The Japanese laity’s hunger for the essentials of Catholic spiritual life—confession, Communion, baptism, pastoral comfort—is so intense that Rodrigues admits it slightly unnerves him. The Kirishitan crave even the smallest physical signifiers of faith, and when Rodrigues runs out of crucifixes and medals to distribute, he breaks apart his rosary and hands out individual beads, each one cradled like a holy relic by the recipient.

Underneath the priests’ marveling, however, is a rumbling of doubt. They cannot understand why God would permit His faithful—particularly faithful that exhibit such ardor—to suffer so terribly. It seems not merely unjust, but cruel, as does the silence they receive in response to their prayers. Garupe grows exasperated with the clandestine and seemingly futile nature of the work, but it is Rodrigues who seems more deeply vexed by the terrible conditions that they have witnessed. When the wrath of the local daimyo eventually descends on the village that has been providing them with sanctuary, the priests are forced to split up. Rodrigues wanders the wilderness in a state of mounting, feverish agitation, allowing impious doubts to pry their way into his thoughts: Is He listening? Is He even there? Am I just praying to myself? His physical weakness and disordered frame of mind make him easy prey for military patrols, and he is soon captured and imprisoned.

It is inaccurate to assert that this is where Silence “really begins”—chiefly because everything in the film’s first half is presented with such breathtaking attention to detail—but it is clear that its more complex thematic aims don’t surface until Rodrigues is in the grasp of the metsuke. The questions that haunt the priest up to that point are fundamental, particularly for a man of the cloth, but they aren’t that different from the theodicy paradoxes confronted by many believers (or, at least, many monotheistic believers), in good times and bad. Violence, disaster, disease, poverty, and even everyday problems can trigger a spiritual crisis in the faithful, prompting the eternal query, “Why does God allow such things to happen?” One hardly needs to be immersed among poor religious minorities during the Edo Period to arrive at such a watershed.

Rather, what Silence’s setting presents are conditions where the believer’s faith is tested on a bloodier and yet more esoteric level. Rodigues and the Kirishitan are urged to renounce their religion under duress, up to an including the threat of death. This shifts the nature of the underlying question from an accusation directed at God (“Why is this happening?”), to an appeal for moral guidance about the supplicant’s own actions (“What should I do?”). For the non-believer, it seems a trivially easy decision: One should say whatever one is obliged to say to stop the pain and save one’s own life. For Rodrigues, however, the dilemma is profound, and not only because the Church regards apostasy as a particularly profane sin. The plight of the Kirishitan that he has witnessed has raised the stakes, so to speak. If the priest cannot, in this time and place and among these people, remain steadfast in his faith, then of what use is his faith? To renounce Christ in these circumstances—when the very existence of the Church in this far-flung land teeters on oblivion’s edge—would undermine the very essence of what it is to be a Christian presbyter.

Silence, then, is in part a film about martyrdom and its ethics, and in this the film shares some affinities with Steve McQueen’s excellent Hunger, a fictionalized depiction of the 1981 IRA prison hunger strike. However, whereas the Irish Republican inmates voluntarily subject their own flesh to a slow-motion violence, Rodrigues has violence unwillingly inflicted upon him by his captors. His martyrdom lies in his refusal to halt this torture, which he can do at any time merely by placing his foot momentarily on a fumi-e, a carved stone image of Christ created specifically for demonstrations of apostasy. The ease with which the pain could be ended makes the temptation especially harrowing. It’s just a little step. What’s the harm?

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that the cunning metsuke knows exactly how to apply pressure to a shepherd: threaten his flock. Accordingly, the lay Kirishitan imprisoned with Rodrigues suffer far more than him at the figurative hands of the Inquisitor. (Ioune himself never stoops to lay a finger on the captives, a neat little detail, given the perceived uncleanliness of torture in the Japanese socio-economic order.) In one of the film’s most shattering scenes, Rodrigues pleads with a group of Kirishitan as they are being slowly bled to death, urging them to apostatize and thereby end their agony. A collaborator then reveals that that the victims have already willingly renounced Christ, over and over. They are being tortured until he, Rodrigues, renounces. The perfect horror of this stratagem is almost too much for the priest to bear.

Rodrigues’ captors erode his resolve with an incessant, disorienting flurry of ridicule, flattery, and patronizing counsel. Ioune even attempts to piteously absolve the priest of responsibility, maintaining that the cultural character of Japan is uniquely unfit for the message of the Gospels. “It’s not your fault,” he soothes, “You were defeated by the swamp of Japan.” Rodrigues, however, sees this as the doublespeak of tyranny. If Christianity is floundering in Japan, it is because of the very repressions that Ioune and his ilk have implemented. The priests steels himself by reminding himself that Jesus endured far worse pain, and that following Christ’s example is the least he can do on behalf of the Kirishitan. Then one of his interlocutors reminds Rodrigues that to compare one’s self to Christ is an unspeakable act of vanity. And so the priest goes, round and round, beleaguered by the obscurity of the righteous path.

Meanwhile, Rodrigues is astonished by the Christians that surround him, many of whom seem to possess a strength of will that echoes the ancient saints. “Why are you so calm?!” the priest demands of fellow captives, his voice halfway between livid and flabbergasted, betraying shame at his own terror. Bound to a cross erected on a rocky shore amid the surf, one Kirishitan survives for four days as the crashing waves pummel him ceaselessly. He perishes singing a hymn, leaving Rodrigues anguished and amazed.

Silence’s most fascinating character by a substantial margin is Kochijiro (Yōsuke Kubozuka), a wild-eyed Japanese drunk who guides the Jesuits from Macau to his homeland early in the film. A reviled apostate, he treads on the fumi-e without hesitation and spits on the cross for good measure, but still regards himself as a Christian. He later sells out his fellow Kirishitan to the metsuke, and eventually betrays even Rodrigues for 300 silver coins—the shogunate’s advertised bounty for a Catholic priest. (This Judas-style perfidy is but one of the film’s many faintly sardonic allusions to the Gospel stories.) Kochijiro in due course evolves into a borderline farcical character, returning to Rodrigues to confess his treachery time and again, and then betraying the Christians time and again. He is consumed with remorse, but seems to have no notion that absolution demands at least a good faith effort at reformation. Stuck in an endless cycle of duplicity and guilt, he undermines the practices of Catholic life through absurd repetition, and thereby drains them of meaning. He haunts Rodrigues, who sees in him a theological enigma: If such a person can call himself Christian with a clear conscience, what does it mean to be a Christian?

Kochijiro’s presence directs the viewer’s attention to a deeper level, beyond the physical and spiritual suffering that dominate the film’s foreground. One could justly regard Silence as film primarily about the narrow matter of Catholic apostasy, and it would be an outstanding film if it were just that. However, such an assessment does a disservice to the richer philosophical questions roiling just beneath the surface of the film, ponderings about human conscience and the limitations of knowledge.

If he only wished to make a historical drama about Christian persecution, Scorsese could have chosen any number of other settings, including the early apostolic period. The specificity of Silence’s time and place is vital. As a Jesuit, Rodrigues arrives in Japan steeped in the intellectual context of the nascent Western Enlightenment, when a new conception of human liberty was being articulated by contemporary philosophers such as John Locke and Baruch Spinoza. (Interestingly, although Dutch by birth, Spinoza was of Sephardic Jewish and Portuguese origin, his ancestors having fled the Portuguese Inquisition, which was propelled overwhelmingly by anti-Semitism. One of the fiercest critics of that Inquisition was the Jesuit philosopher and missionary António Vieria. Connections upon connections...) The world into which Rodrigues tumbles is as far removed from Western proto-liberalism as one could imagine. Japan’s distinctive hybridization of an animistic Shinto worldview with Buddhist religious and philosophical traditions mark it as truly confounding territory for the likes of a European Jesuit. The priest’s circumstances are, in a sense, ideally suited to a grisly discourse on freedom of thought.

Beyond the theological arcana of its central dramatic conflict—To apostatize or not to apostatize?—Silence is concerned with the unassailable and unknowable character of the human mind. While freedom to practice one’s religion can be curtailed by an oppressive government, the freedom to believe is a trickier beast. Given that no one can ever truly know for certain what is concealed in another person’s heart, there is no way to reliably verify if apostasy and conversion are fraudulent. Indeed, this vexing constraint is precisely what drove the Portuguese Inquisition. Its leaders were suspicious that the kingdom’s tens of thousands of Jewish converts to Catholicism were faking their newfound devotion. The shogunate’s agents can torture Rodrigues until he howls all manner of sacrilege, but they cannot peer into his mind and spot-check to see if he has truly abandoned God.

The paranoia that such uncertainty breeds in the oppressor is illustrated in the film’s coda. Once Rodrigues steps on the fumi-e, he is released and treated relatively well, but the shogunate never abandons its distrust entirely. Bestowed with an executed man’s house, complete with Japanese wife and child, the now-fallen priest is obliged to submit an annual written renouncement of Christianity, and he and his retainers are watched carefully. The shogunate has “won” in the sense that Rodrigues has forsaken his faith and does all that is asked of him for the rest of his life, but his hosts can never be absolutely sure of their victory. The film’s final shot, revealing a minuscule wooden crucifix that Rodrigues’ widow has surreptitiously tucked into the dead man’s hand prior to his cremation, suggests that their suspicion was justified. Conversion at the point of a sword, after all, would seem to rob the concept of conversion of all its meaning. This is reflected in the contemporary understanding of physical coercion’s poisonous effect on the captor-prisoner dynamic; what one might call the pragmatist’s critique of torture. To inflict pain on a prisoner as a means of interrogation or compulsion is to forever mark the captor as an enemy.

One of Silence’s most striking and unexpected aspects is the ease with which its layers of meaning—theological, cultural, political, psychological—are peeled away, revealing the metaphysical disquiet that lurks at its core. With remarkable subtlety, Scorsese has in some respects smuggled a story that transcends religion into an intensely religious film. Its agitations concern the fundamental problems of categories, concepts, and the self. If a person asserts they are no longer a believer and lives as if are no longer a believer, in what sense, if any, can they be considered a believer? If belief is locked away forever in a secret place, if it ceases to have any concrete effect one’s life, can it be said to exist at all? What does one even mean by words such as “belief” and “believer”?

While such abstract matters might seem relatively academic when considered alongside the prospect of personal damnation or the torturer's cruelties, they are the foundational questions of the human experience. Indeed, Silence’s presentation of the Japanese state’ brutality signals the film’s interest in such profound topics. The torture and execution methods that the Japanese authorities inflict on their captives are not dependent on the baroque instruments of pain associated in the imagination with the royal jailers and religious inquisitions of Renaissance Europe. The shogunate’s weapons are simple and elemental: fire, water, blood. Such primeval tools of coercion reflect the potentially impenetrable questions of being that flit just beyond the periphery of Rodrigues’ spiritual torment.

This metaphysical dimension to the film’s thematic topography is most apparent when a pre-apostasy Rodrigues comes face to face with his former teacher, Ferreira. It is a meeting that is extensively foreshadowed in the film, but when the moment finally arrives, Rodrigues is taken aback by the extent of Ferreira’s transformation into a Japanese man in every sense but birthplace. The former Jesuit contends that the Christianity practiced by the Japanese is not actually Christianity at all, but a folk religion with Christian trappings, the accumulated result of countless errors and modifications. Humans, after all, routinely mistranslate, misconstrue, and misremember, particularly when there is no clerical oversight to maintain orthodoxy. What Rodrigues means when he says “God” is not what a Kirishitan understands when they hear “God.” The hundreds of thousands of Christian converts that Rodrigues believes once existed during the faith’s 16th-century heyday are, Ferreira contends, essentially a fiction.

(Neeson’s performance in this small role is a thing of wonder, not the least because Ferreira’s demeanor evolves in a counter-intuitive way over the course of the conversation. He starts out awkward, almost embarrassed, and gradually becomes more strident and unyielding as he parries Rodrigues’ objections to his apostasy. A different species of religious film would conclude with Rodrigues the rhetorical victor, having shown the elder, humbled Ferreira the error of his ways.)

Ferreira’s criticisms expose the universal uncertainty that characterizes the human condition. If two parties cannot even agree what words mean, how can one presume to busy themselves about the business of the soul? There is even a meta-textual aspect to Ferreira’s words, a critique directed at Silence itself. Scorsese’s feature is an adaptation of the Japanese historical novel of the same name by acclaimed Catholic writer Shūsaku Endō. (The book was also previously adapted into a 1971 Japanese film by director Masahiro Shinoda, which almost certainly influenced the famously cinephilic Scorsese). Thus, Silence is a 2016 English-language American cinematic adaptation of a 1966 Japanese-language novel about the expression of a Western religion of Bronze Age Near Eastern origin in 17th-century Japan. The mind fairly boggles at the potential mutations inherent in such an epic, multi-lingual transmission.

Indeed, there are numerous ways in which Silence is muddied in a cerebrally gratifying way by its status as a modern story being told for a modern audience. One can discern a potential existentialist reading of the film, for example, in which a silent God is functionally indistinguishable from an absent God. Rodrigues’ plight can then be regarded as that of a man who is “condemned to be free,” in the Sartrean sense, wherein he and he alone is wholly responsible for his actions. What’s more, freedom of thought as it is understood in the classical liberal sense is thrown into question in a contemporary world of pharmacological alteration and the shrewd psychological manipulations of advertising and propaganda. All of this is to say that while Silence is a magnificent work when approached solely as a Catholic film about overwhelmingly Catholic spiritual concerns, it becomes infinitely richer when one gives its multitude of potential meanings and readings sufficient space to breathe.