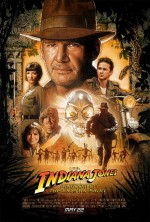

2008 // USA // Steven Spielberg // May 26, 2008 // Theatrical Print

C - Let's get the Bad News out of the way first: Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is the weakest chapter to date in the now-grizzled archeologist's adventures. To put that statement into context, consider that I have stubborn admiration and affection for the series' previous low point, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Given the mark the original trilogy left on my young mind, and given that it's been so long since Harrison Ford last took up the fedora and bullwhip, I'm finding it somewhat difficult to put the new film into the proper perspective. What I can't deny is that there's a sense of melancholic disappointment to Kingdom, a sharp slap of reality that fades to a lingering sting. It's like running into a an old schoolmate after nearly twenty years apart, and finding that the former star athlete and class president is now a termite inspector living in a trailer with five kids. Kingdom is a fine adventure film, and it superbly accomplishes its tricky task of updating the series for a new age. Yet there's something a little shocking and unwelcome about unearthing a new Indy film at long last, only to discover that, in many ways, it's just another action-film-as-amusement-park-ride in a bloated summer season.

It's 1957 in Indy's world, and the long winter of the Cold War has arrived. The Soviets have supplanted the Nazis as the villains du jour, but Dr. Henry Jones, Jr. is still alive and kicking. Since we last saw him, the professor of archeology has grayed and plumped some, settling more comfortably into his daylight role as a befuddled academic. When the film opens, however, our first glimpse of Indy is that dusty and beaten fedora that serves as a talisman for his less savory, more thrilling pursuits. Indy and fellow relic hunter Mac (Ray Winstone) are hauled from the trunk of a car and held at gunpoint at an Air Force hanger (Number 51, naturally). Their captors are Soviet spies, commanded by porcelain-skinned femme fatale Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett), who demands that Indy locate a particular crate inside the hanger. No, not that crate, although it does make a cameo appearance. Treating the Ark of the Covenant as a throwaway gag might be uncomfortably glib, but it serves to underline the shift in the series' tone. The tyrants of the Cold War are not enticed by anything as provincial as an occult artifact. They crave nothing less than the secrets of the stars. Indy reluctantly helps the Russians retrieve their mysterious prize, but of course he eventually slips from their grasp, in a gloriously ridiculous sequence capped with one of the film's truly unforgettable visuals.

Indy returns to his college, where his cooperation with the Russians—under duress, but no matter—prompts some to question his loyalties. Eventually, a motorcycle-riding delinquent named Mutt (Shia LaBeouf, decked out in leather and pomade) tracks Indy down and pleads for his aid. The Russians have kidnapped the greaser youth's mother, as well as archeologist Harold Oxley (John Hurt), a father figure to Mutt and an old colleague of Indy. Oxley knows the location of a legendary crystal skull, an allegedly pre-Columbian artifact with mysterious powers, and the dread Agent Spalko is, naturally, seeking it with supervillain fanaticism. It's fairly pointless to get into the plot details, given that Indy explicates the academic mumbo-jumbo and connects the dots for us, as usual. At any rate, the plot is just an excuse for a bunch of action set pieces, right? In Kingdom, we get a motorcycle escape through a New England college campus; a brawl in an Air Force weapons research facility; a crawl through a Peruvian mummy tomb; a car, truck and boat chase in the Amazon rainforest; and the opening of the gates of fabled El Dorado.

Are these action sequences any good? Yes, in that they're always entertaining and often quite thrilling. Are they on the same level as Last Crusade's tank chase, Temple of Doom's bridge standoff, or anything at all in Raiders? Nope. The computer-generated mayhem of Kingdom lacks the sense of genuine danger that Steven Spielberg achieved in the previous films using old school stunt work, pyrotechnics, and camera trickery. Granted, the original trilogy contains the occasional matte or puppetry effect that looks downright embarrassing nowadays. Yet Kingdom is so littered with digital effects—literally from the very first shot—that the film seems to suffer for it. Part of this may be that its effects are, well, substandard. When you've seen The Lord of the Rings and Transformers recently achieve miracles of digital visualization, LaBeouf's vine-swinging in Kingdom comes off as distractingly bogus. I'm trying not to be hypocritical here. Gleefully fake action can suffice in fluffy, post-Indy fare like The Mummy, or as a deliberate stylistic choice in pseudo-auteur popcorn endeavors like Speed Racer. But this is Indiana Jones, for crying out loud. He deserves better, and I know damn well it's possible when Spielberg's own War of the Worlds set a higher bar three years ago.

Then there's the dialogue, which just isn't very good. I didn't expect anything close to Lawrence Kasdan's amazing screenplay for Raiders, but I was hoping for something on par with Temple or Last Crusade. Alas, Kingdom just isn't as touching, brisk, or witty as its predecessors. That last item is a particular problem. Many of the film's "jokes" fall flat, partly because they're simply not funny, partly because Winstone, LaBeouf, and Ford (regrettably) don't put much of a shine on them. Tellingly, I had a hard time discerning whether it was Ford or Indy that's become a tired, humorless fart. (The latter might be excused as a distressing but valid evolution of the character, while the former is just bad craft. I tend to favor the more charitable explanation) The dialogue doesn't fare much better when it gets sentimental, and the alternately hazy and hackneyed secondary characters just make matters worse.

As you probably know by now, Karen Allen is back as—surely we can all agree?—Indy's greatest female foil, Marion Ravenwood. Thanks to the clunky screenplay, Marion's return isn't addressed with the grace or pathos it deserves, but at least Allen finds an appropriate tone. Marion's credible swagger and low tolerance for bullshit are still intact, but Allen dilutes the character's youthful venom and finds a fitting middle-aged softness and longing.

Given all these problems, what's good about Kingdom of the Crystal Skull? Well, for starters, it's a new Indiana freaking Jones movie. I like to think that I'm discerning enough to reject a turd in a box from Spielberg with the words "Indiana Jones" on it. And my initial impression is that Kingdom isn't even in the upper half of Spielberg's filmography. Yet Kingdom is no exception to the rule that Spielberg is a natural talent when it comes to the language of film. Even on his off days, his composition and his flair for storytelling are something to behold, and at its best Kingdom is another brick in Spielberg's artistic reputation. It's certainly not a self-contained legacy the way Raiders was, but I think that time will generally be kind to its striking beauty and sharp pacing, in the same way that Temple and Crusade have aged well.

Furthermore, I can safely say that Kingdom is further confirmation that George Lucas is an Idea Man, whose strength will always be the creation of worlds rather than films. In contrast to Star Wars, here the creaky dialogue can't be laid at his feet, nor can the lackluster performances. But the Indy stories are his and Kingdom's is an unexpected coup. I was skeptical about the film's aim to update the Indiana Jones franchise for the 1950s. To launch Indy into a new era after such a long absence is, in a word, brave. The shift in tone takes some getting used to, but the story feels compelling and fresh, a diversion into the territory of Cold War thrillers and science fiction rather than 1930s pulp. It's a gamble, but for me the atomic terror, psychic spies, and alien technology came together. In a way, Kingdom feels like an intriguing slice of Indiana Jones fan fiction, save that it comes courtesy of the original creators and stars. The only downside is that our long absence from Indy's world covers so much time that one can't help but feel a bit cheated by all the interesting stuff that's happened off-screen. ("Wait, Indy worked for military intelligence during World War II? Can we see that?")

Blessedly, the tweaking of Indiana Jones' genre trappings doesn't feel forced or frivolous, like some kind of "Sherlock Holmes in the 28th Century" speculation. If there is a bit of awkwardness to Kingdom's alignment with the realities of a new setting, there's also a clear recognition that cultural icons are creatures of a specific time and place. Some discomfort is to be expected. This is what makes me more inclined to forgive the harder, more petulant edge to Indy in this outing. The Indy of the 1950s is less a man of bravado than a scarred and foul-tempered bulldog. This is the most conspicuous change in the character: he just isn't as charming as he used to be. It's saddening, but also somewhat understandable. Two decades of frantic globetrotting, a Second World War, and the chill of the Red Scare would wear down any man.

More crucially, Kingdom also boasts a satisfying awareness of its place in Indy's character arc. Unlike the man he portrayed in the original trilogy, here Ford plays Indy as a veteran hero with little need for newly minted wisdom. He is weary and cantankerous, but he also feels complete, excepting perhaps a family to share his later years with. The older Harrison Ford fumbles Kingdom's ill-conceived attempts at humor, but so what? To his credit, Ford knows exactly where his character is in 1957. We get a strong sense of a resilient old man with the foolishness and narcissism distilled out of him. Indy gets to show off his breathtaking anthropological knowledge like never before, and he's presented with opportunities to provide direction and wisdom to others. Kingdom offers what seems like heresy for the series, but upon reflection only makes sense: a vision of a man changed by the harrowing events that have come before. This is first Indy film that is occupied not with the hero's struggles with desire (that ever-tantalizing "fortune and glory"), but with his awakening to his true needs. In a telling and wonderfully insightful twist, Kingdom's story hinges not on the plundering of a relic, but its return to its rightful place, an oblique indictment of the previous films' colonial undercurrent.

My expectations for Kingdom of the Crystal Skull were, in a way, the complement to the film that I got. I anticipated an exhilarating Spielberg epic whose break with the Indy films of old would be its downfall. Instead, I discovered a thoroughly B-grade summer action flick whose most enthralling feature is its audacious updating of an allegedly sacred American pop mythos. As with all the Indy films, I think that Kingdom will grow on me. However, I also suspect that the fourth film's place in the Indy Canon will always be shaky. The mediocre effects, dialogue, and acting lend it a sad staleness. Its redemption lies in its persuasive determination to blaze new paths with its hero, Spielberg's eye for transfixing imagery, and the fact that in the final analysis, it's still a fun action film.