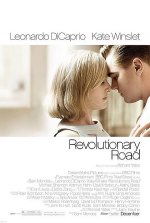

Scenes From a Marriage

2008 // USA - UK // Sam Mendes // January 10, 2009 // Theatrical Print

B - With Revolutionary Road, director Sam Mendes once again takes up the spiritual stultification of the middle class. However, where his American Beauty was thematically preoccupied with suburban banality, here Mendes employs it as a plot element and motif in a far more pointed work, one that is part character study and part time capsule of toxic gender dynamics. The script--here adapted by novice Justin Haythe from David Yates' novel--features some teeth-grittingly awful dialog, and yet Mendes' direction is so forceful, and the lead performances from Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio are so enthralling, that it doesn't much matter. Striking in its awareness of emotional details and its eye for potent visual poetry, Revolutionary Road is a fine example of the sort of film whose heady highs linger longer than its clunkier features. In creating a portrait of a love gone gangrenous and insidious misogyny in full flower, Mendes offers a cinematic drug distilled from pure human venom. Damn if it doesn't hurt so good.

Following a brief prelude where we glimpse their fresh-faced first encounter, the film leaps forward by years and plunges neck-deep into the fraying marriage of dissatisfied 1950s suburbanites Frank and April Wheeler. April's swelling sense of entrapment in her dreary housewife routine is highlighted by a wretched performance in a community theater production. Frank, meanwhile, is bored and emasculated (that word will come up a lot) in his colorless city job where he writes marketing materials for a business machine company. Things weren't supposed to be this way. Once, they had ambitions higher than promotions and new appliances. They sneered at greed and middle class conformity. They wanted to "feel things," a gloriously vacant formulation for every morsel of vain restlessness that Frank and April harbor.

Mendes drizzles the film with flashbacks to hint at the vanished optimism and anxious cravings that once characterized the couple. The contrast is stark, but the film's answer to the Wheelers' plaintive question—What happened to us?—is more cutting than a rote condemnation the spatial and cultural environs of suburbia. Therein lies the genius in Yates' selection of his protagonists: Frank and April believe themselves superior to their neighbors and co-workers by virtue of their sensitivity to their own spiritual plight, but that same intelligence makes them cunning manipulators and obfuscators. For all of Revolutionary Road's meticulous design—its hunger for period detail, lit in glowing hues, is almost almost fetishistic—and its occasional snickering at the emotional phoniness of its setting, the film is not truly a screed that targets middle class institutions. Indeed, one senses that Mendes is counting on his audience to have already internalized the facile cultural tongue-clucking of American Beauty, such that Revolutionary Road wallops the viewer all the harder.

The ugly proposition at the heart of the film's narrative—that Frank and April are cowardly, selfish, dimwitted moral cripples—is both pleasingly conventional and remarkably bold after a fashion. The Wheelers are engineered to elicit identification (if not sympathy) from the viewer, which makes it all the more traumatic when their miseries are eventually revealed to be of their own making, rather the product of a monolithic social monster. It's a risky move to lacerate your audience with implicit yet intensely personal indictments, but Mendes succeeds both because of the distance that his historical setting provides and because, frankly, he has our number. The casting of Winslet and DiCaprio proves to be a fascinating metatextual stunt, given the cultural saturation of their previous collaboration in Titanic as a storybook couple ripe for wishful projection. While there is little hint that Frank and April are intended as a direct, cynical refutation of Jack Dawson and Rose Bukater's thwarted life together, the connotations at play in the selection of these particular performers are both deliberate and satisfying.

From a succession of crises and scuttled plans, Mendes manages to sculpt one of the starkest portraits of soured love and sneaky sexism in recent memory. It's Train Wreck interpersonal drama—so horrible you can't look away—but it achieves more than ugly entertainment thanks to DiCaprio and Winslet's searing portrayals. There's also an undeniably compelling novelty in seeing the nasty aspects of the Good Old Days, particularly its misogyny, portrayed without glibness or cartoon villainy within a decidedly soapy plot. Indeed, Revolutionary Road is a brilliantly deft depiction of the nature and ugly consequences of patriarchal norms, if only because it dares to embody them in an ostensibly hip, intelligent man.

Kate Winslet is, well, just fucking fantastic here, undeniably one of the best performances she's ever delivered. There is no other English language actress of her generation who has the ability to invest even the most laughable lines—and Revolutionary Road unfortunately has those in spades--with such dramatic allure and emotional credibility. With his consciously boyish insincerity and emergent flair for scenes of apoplectic rage, DiCaprio proves to be a perfect foil to Winslet's blend of crisp assertiveness and flailing, emotional free-fall. Frank is certainly the most unlikeable and intricate character DiCaprio has ever tackled, and he more than rises to the occasion. Not to be overlooked is the reliably memorable Michael Shannon, whose drill sergeant jaw and nail-head eyes are used to excellent effect as the mentally ill adult son of a neighbor. There's something a little too tidy about the presence of his character in the story--for you see, only an insane man has the courage to speak the rotten truths of 1950s suburbia. Nonetheless, Shannon captivates for every moment he's on screen, and he lays claim to the screenplay's most searing line.

Revolutionary Road is such marvelous meshing of character, theme, and direction, it's all the more unfortunate that the film's dialog is often quite bad. Not consistently so, mind you, but still howlingly bad in its worst moments. It's not clear whether Haythe is attempting to capture a stilted tone that he imagines predominated middle class conversation five decades ago, or whether he just has no idea how human beings talk in private conversation. The dialog is outright distracting in its awfulness in spots, and it takes quite a bit to distract from Kate Winslet. There will likely be countless comparisons between Revolutionary Road and Mad Men, if only due to their similar milieu and concurrent appearance in the cultural zeitgeist, but the crackling dialog in AMC's television series is generally a cut above anything in Haythe's screenplay. The dialog problems and Mendes' childish tittering at all the Better Homes and Gardens banality on display render Revolutionary Road as something substantially less than a triumph. Yet there's no denying the worth of the film as a dose of pure, discomfiting human drama, crowned with a pair of utterly engaging performances.