What's It Like to Be the Bad Man?

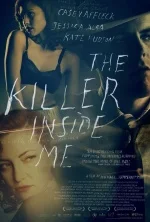

2010 // USA // Michael Winterbottom // July 12, 2010 // Theatrical Print (Landmark Plaza Frontenac)

B - Michael Winterbottom's adaptation of Jim Thompson's 1952 noir novel The Killer Inside Me is not an enjoyable film, at least as one usually applies the term to a movie-going experience. Nor is it without vexing structural flaws. And yet it is an undeniably fascinating work, an absorbing and unnervingly insistent portrayal of a murderous mind that joins the ranks of cult notables such as Mary Harron's American Psycho and John McNaughton's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. However, the gaze of Winterbottom's film reaches back to a more distant point. Specifically, to Psycho, whose particular cinematic genius the film cannibalizes and assimilates into its own strange approach. Working from a screenplay by director John Curran, Winterbottom maintains a literate awareness of Hitchcock's seminal thriller throughout his film, without resorting to shameless appropriation or self-conscious homage. Thompson's novel has made the jump to the screen before, in a 1976 Stacy Keach vehicle directed by Burt Kennedy. However, the new film does not carry the telltale odor of a flimsy remake, nor that of an adaptation overly beholden to its source material. This new take on The Killer Inside Me is insolent and distinctly cinematic. It ambles along a lurid, eccentric path on an unsettling mission: to convey both the hideous normalcy and incomprehensible disconnection of the psychopathic mind.

The film presents the tale of Lou Ford (Casey Affleck), a clean-cut, gawky deputy sheriff in rural 1950s Texas. Lou doesn't carry a service revolver; the most hazardous part of his job entails placating local bigwigs such as construction mogul Chester Conway (Ned Beatty) and union boss Joe Rothman (Elias Koteas). Lou is well-mannered and soft-spoken, a country boy who spends his nights reading while listening to opera, when he's not romancing his sweet-as-sugar girlfriend, Amy (Kate Hudson). Lou is also a coldblooded murderer, as the film's title and promotion make abundantly clear. Where you or I have empathy and remorse, Lou has... nothing. He's a Hollow Man. In flashback, we learn that Lou's masochistic mother nurtured a streak of sexual sadism in the boy from a young age. It's not clear whether this abuse stunted Lou's moral development, or merely exacerbated what was already a disturbed mind. It doesn't really matter. There's no struggle between saint and sinner beneath Lou's canted Stetson; he's a monster through and through. The only tribulation that he even seems to acknowledge is the sheer challenge of evading capture for as long as possible. Fortunately for Lou, he's an excellent liar, the sort of aw-shucks bullshit artist who can improvise on cue and has an answer for everything.

In the film's opening scenes, the sheriff (Tom Bower) sends Lou off on something of a shit task: convince a local prostitute, Joyce (Jessica Alba) to pull up stakes and leave town. Lou's confrontation with the woman escalates to a brutal assault that satisfies his taste for sexual violence, and then turns on a dime into a bout of mutually enthusiastic screwing. The pair begin to make a regular thing of this game, but complications ensue: one of Joyce's clients is Elmer Conway (Jay R. Ferguson) the lunkhead son of the aforementioned construction mogul. Daddy Conway wants Lou to act as a bagman and pay off the whore who has beguiled his son. Instead, Lou hatches a scheme wherein Joyce will abscond with Elmer and the money, then ditch the dupe and rendezvous with Lou later. Incidentally, Elmer's shoddy construction work may or may have not resulted in the death of Lou's half-brother, a fact that the union boss uses to tweak the deputy. I said it was complicated, didn't I?

Ultimately, this elaborate and often aggravating plot is essentially just the set-up for Lou's sudden and unspeakably brutal betrayal of Joyce, whom he beats to death in one of the film's most disturbing and audacious scenes. Not that violence perpetrated by men against women is all that uncommon in cinema, but it's rarely portrayed as unflinchingly as it is here, without the glamorization or weird elision that characterizes action film editing. Instead, what we get is several nearly unbearable minutes of a man pounding the head of a defenseless, essentially unresisting woman into bloody hamburger with his bare fists. This is presented with the steadiness one might normally exhibit when observing a man painting a fence. Right about now, you probably already have a fairly robust notion of whether there is any chance in hell of you ever seeing this film, so there's not much point in attempting to convince the doubters that this graphic violence is essential, even if it is repulsive. However, I will proffer that it enhances the dissonance that pervades the rest of the film, which is mainly concerned with the lengths that Lou must go to in order to conceal his role in the murder. He has to tell lie after lie, attempt to rectify a handful of crucial blunders, and commit more crimes, whose cover-up demands still more crimes, and so on.

Winterbottom's model here is, of course, Psycho, with its superbly cunning shift in sympathy from the slain femme fatale to the quiet man who is protecting her murderer. The savagery of Lou's violent impulses only heightens the film's rising sense of disorientation and gnawing unease. "This guy can't be the story's hero, can he?" Eventually, it becomes apparent that there are no heroes in this world, not even a laconic private eye to ferret out Lou's sins. The deputy's antagonists are a smug district attorney, an opportunistic vagrant, and that devious union boss. (The latter leans on Lou with his Peter Falk routine, but he isn't looking out for anyone but himself.) Winterbottom offers no emotional handholds in this story but those that project from Lou himself, which I suppose is a kind of artistic sadism, but also magnificent in its ruthlessness. Following along from a monster's point of view engenders a sense of helplessness that is only enhanced by Affleck's performance. Lou is languidly charming in public, urgent and vicious in the bedroom, and coolly blank in private. He is a cipher, and doesn't ask for or want our understanding. The film hints at what might be going on behind those reptilian eyes—finding dirty pictures of his mother in a family Bible, Lou calmly burns them—but there is no psychologist to offer a concluding exegesis here. We can only sit in stunned silence and wonder at how a human brain can break so bad.

The flaws that afflict The Killer Inside Me are mainly pacing problems. They are particularly conspicuous following a pivotal murder, after which Winterbottom seems to lose his capacity for linking scenes together coherently. The passage of time becomes ambiguous, and the story begins to feel disjointed and even clumsy. More generous viewers might regard this as consistent with the delusional aspects of Lou's madness, which eventually begin to intrude directly into the film. I'm inclined towards the simpler explanation: standard-issue third act narrative aimlessness. That said, the corrosion of reality is perhaps inevitable in any work that approaches madness from a first-person perspective. Curran's screenplay indulges in escalating strangeness as Lou's final fate draws near, and by the time it descends into soap opera silliness, it's abundantly clear that the film has fractured to match the deputy's mind. We're dwelling entirely within Lou's diseased headspace by the end, and the events that unfold reveal a vacant mind that echoes with obsessions, a place where virtuous love and violent depravity have the same tune.