2013 // Canada / Spain // Denis Villeneuve // March 29, 2014 // Digital Theatrical Projection (St. Louis Cinema Chase Park Plaza)

[Note: This post contains moderate spoilers.]

A nauseating yellow pall clings to every inch of Canadian director Denis Villeneuve's horrifically unsettling new feature, Enemy. The hue feels both toxic and suffocating, as though the film’s events were enveloped in a sulfur smog. This sort of domineering color correction has become so commonplace in cinema—witness the triumph of the dreaded orange-and-teal—that it is notable when a film aggressively employs it for a purpose actually related to storytelling. The omnipresent jaundice haze that cloaks Enemy evokes contagion, contamination, and fungal rot. It is the color of bile on a sickbed sheet. It implies a threat, but one that is concealed, like a cancer that reveals itself only through a nagging cough and gnawing fear.

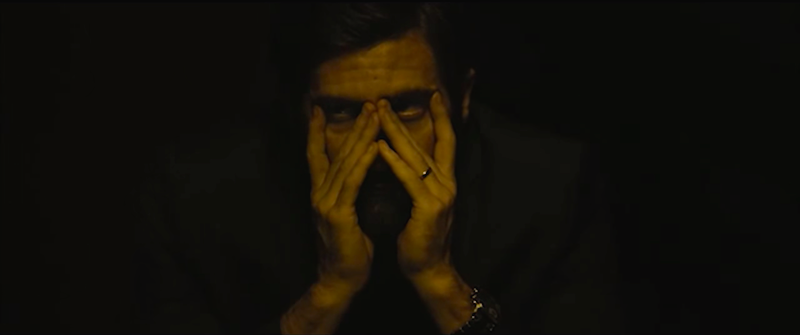

This repulsive tinting is merely one aspect of the film’s style that nurtures a potent and relentless sense of unease. That mood is seeded by the film’s enigmatic and strangely menacing first scene, in which a intense, bearded man (Jake Gyllenhaal) follows a shadowed corridor to a guarded door. Passing the gatekeeper, he enters a dim chamber where an underground sex show is underway. Patrons look on impassively as some sort of outré performance unfolds just offscreen, its erotic character clear but its details indefinite. However, things become startlingly specific when a silver serving tray is produced and then uncovered, revealing an enormous live tarantula. A performer raises a heel and holds it pointedly over the arachnid, while the newly arrived man sits with his head in his hands, peering out in dull fascination and profound self-disgust.

This bizarre opening sequence is always lurking beneath the surface of Enemy. It is a promise that every secret thing will be unearthed in time, lending a touch of fearful expectation to the events that follow. The viewer is next introduced to the sad, shuffling routine of Adam (Gyllenhaal again), a history professor in a nameless city. In a university lecture hall dotted with too-few students, Adam holds forth on the cyclical nature of humanity’s endless struggles. He quotes Marx’s observation, “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce,” and describes the rise and fall of totalitarian powers. Bread and circuses are key, he notes, to keeping a populace distracted from their diminishing liberties.

Adam seems to be caught in a tedious, conformist loop, the radical flavor of his teachings notwithstanding. He lectures, goes home to his little apartment, grades papers, eats dinner, and has sex with his girlfriend Mary (Melanie Laurent), sometimes vacantly, sometimes desperately. Each day Adam performs the same mundane rituals, and then next day as well, such that time begins to seem jumbled and slippery. Mary appears to be his only human connection, and even that relationship feels weirdly distant and awkward, as if they are both biding their time. During the early hours one night, he attempts to rape her as she slumbers beside him, to her understandable shock and anger. Adam seems as surprised as her.

One day, apropos of nothing, a fellow faculty member recommends a movie, and Adam reacts with the dazed awkwardness of a man with only minimal exposure to pop entertainment. He sheepishly seeks out the DVD at a local video store, and while Mary sleeps he watches the film on his laptop, like a teenager clandestinely browsing porn on his mother’s computer. The movie proves banal, until Adam witnesses a sight so strange that he has to rewind and look again: an actor in a bit part who could be his identical twin. The sheer uncanniness of this discovery is the jolt that dislodges Adam from the monotony of his existence. The actor in question, Anthony (also Gyllenhaal), becomes an obsession for Adam, a target for energies that had previously kept the academic moving in listless circles.

Like an overgrown Hardy Boy, Adam tracks down his doppelganger with some amateur sleuthing. Donning a pair of dime store sunglasses, he bluffs his way into Anthony’s talent agency by impersonating the actor. Eventually he secures the man’s home address and phone number, and is soon lurking outside Anthony’s building, counting off windows in an effort to identify the man’s apartment. Initially, a kind of perturbed curiosity drives Adam to seek out his double. He harbors a vague hope that the man will have the answers that he does not. Adam is vitalized by the thrill of playing detective, recalling Betty’s giddy exhortation in Mulholland Drive: “It'll be just like in the movies. Pretending to be somebody else.” (In his enthusiasm for a mystery, Adam also echoes Gyllenhaal’s Robert Graysmith from Zodiac.) However, when Adam places a fumbling phone call to Anthony’s home, the actor’s pregnant wife Helen (Sarah Gadon) answers and mistakes the professor’s voice for that of her husband. Thereafter, Adam begins to seem increasingly unnerved by the situation. By intruding into his duplicate’s life, he has created a conjunction between their formerly distinct worlds, an overlap that will inevitably result in an upheaval.

Adam and an irritated Anthony eventually speak directly, and their overheard phone call picks at Helen’s suspicions. Anthony tries to reassure her that Adam is just a starstruck weirdo, but she suddenly asks, “Are you lying to me?” (Gadon’s delivery of this line, her eyes narrowing subtly, is downright flawless.) A kind of knowing fearfulness clings to Helen’s reactions. One senses that Anthony has had ample practice at deception, above and beyond what is required for his profession. Without her husband’s knowledge, Helen goes to the university campus and lingers near Adam’s department until she crosses paths with the professor. Instead of identifying herself, Helen can only gape in astonishment at this man who wears her husband’s face. “He looks exactly like you,” she later reports to Anthony, and then pleads, “What’s happening?” “I really don’t know what you’re talking about,” is his baffled reply. In a voice dripping with cold terror, she can only respond, “I think you know.”

Indeed: What is happening? Enemy is remarkably coy about what sort of story it is spinning. The film has the motifs and rhythms of a thriller, certainly, but its essential nature is fiendishly ambiguous. It could be a psychological portrait rendered from an unreliable viewpoint. Or a folk nightmare given a fresh coat of contemporary magical realism. Or an allegory on the insidious qualities of authoritarian control. The source material’s provenance suggests that the latter in particular. Screenwriter Javier Gullón adapted the script from the novel The Double by Portuguese writer and Nobel laureate José Saramago. A communist of libertarian bent, Saramago grew up and dwelled for decades under the boot of his nation’s fascistic Estada Novo government. Unsurprisingly, he often worked pointed political critique between the lines of his darkly absurd stories. While Gullón alters The Double’s plot and tone for his adaptation, the trappings of radicalism and reactionaryism are scrawled in Enemy’s margins. Adam’s blackboards are covered in the argot of deconstructive philosophy, public spaces are splashed with Bansky-style graffiti of saluting corporate clones, and the sex club operates with the deadly-serious secrecy of a French Resistance or Red Army Faction cell.

Villeneuve’s work is inclined towards the bloody and the pessimistic, and often focuses on the realization of political ideology through intensely intimate acts of violence. Collective and personal guilt also figure prominently in the filmmaker’s recent films: Polytechnique, a chilly recreation of the 1989 anti-feminist Montreal Massacre; Incendies, a preposterous but engrossing fable of Middle Eastern sectarianism; and Prisoners, a bleak, Hollywood-slick crime thriller simmering with God-hating rage. Enemy shares the latter feature’s high level of stylistic polish, but its formal and thematic sophistication marks it as a fresh achievement within Villeneuve’s filmography. Using just a handful of performers and a relatively lean script, the director conjures a mood that is at once primal and cerebral. It seeps like cold water through the cracks in the viewer’s rational mind. Once inside, it expands into an intricate dendritic pattern of political, social, and sexual fears.

Adam and Anthony descend from a fertile lineage of imposters and replacements in the mystery/thriller genre. Vertigo is an obvious touchstone for any film in this category, and like Kim Novak’s object of desire, both Mary and Helen are blondes with an unsettling effect on the men in their lives. There is firmer precedent in Brian De Palma’s oeuvre, which is particularly flush with duplicates (Sisters, Obsession, Body Double, Raising Cain, Femme Fatale), and with protagonists who, like Adam, engage in ad hoc detective work. (Adam’s first phone conversation with Helen even echoes the call that philandering Sherman McCoy mistakenly makes to his own home in The Bonfire of the Vanities.) For all their lurid excesses, however, De Palma’s films unfold in a world where the seemingly inexplicable is always revealed to be an illusion conjured in the name of greed, revenge, or perverted love. The pulpy reality of such features is far removed from the alienating, dread-choked world depicted in Enemy.

Villeneuve’s film lies closer to the nightmarish realms of Roman Polanski, David Cronenberg, and David Lynch, all of whom have explored the horror potential of changelings, fetches, and doppelgangers (of a kind). Even a cursory examination of Enemy reveals bits of Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, Dead Ringers, Naked Lunch, Eraserhead, Lost Highway, and the aforementioned Mulholland Drive. Enemy’s closest kin is perhaps Polanski's The Tenant, an eccentric (and often funny) horror feature that explores similar themes of paranoia, dominance, and entrapment. Replication and repetition are also significant aspects of both films, which evoke the distinctive, fatalistic despair that can accompany deja vu. Like Twin Peaks’ Giant, this sensation intrudes into the present moment to declare portentously, “It is happening again.”

More so than any particular plot elements or theme, however, it is Enemy’s nearly smothering atmosphere of fear that places it firmly in an esteemed tradition of quasi-surrealist horror cinema. Villeneuve exhibits an impressive facility for turning the most mundane urban locations into reservoirs of awful, gut-twisting dread. Aside from the film’s venomous yellow hue, Enemy’s fantastically unnerving score is the most conspicuous means by which this mood is achieved. Composers Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans create a soundscape that is cold-blooded yet constantly in motion—slithering, creeping, and scuttling. Permeated with lonesome woodwinds, groaning strings, and staccato screeches, Enemy’s world seems a place devoid of calm or repose.

The extraordinary compositions crafted by Villeneuve and cinematographer Nicolas Bolduc are also deeply essential to the film’s oppressive aura. Enemy’s visual vocabulary contains abundant straight lines and polygons, but few curves. Characters are frequently boxed in from all sides by rigid planes of glass, metal, plastic, and concrete. Overhead, power lines criss-cross to form a looming wire canopy, amplifying that sensation that even outdoors, humankind is caged. Dismal, modernist high-rise apartment buildings tower over the landscape like long-cold industrial furnaces. From a God’s eye view, these monoliths reveal a secret geometry, the stone and steel tessellated into patterns. The film’s cityscape feels at once organic and alien, as if humankind were dwelling in the ruins of a lost insect empire.

Laurent, Gadon, and Isabella Rossellini (as Adam’s mother) each add a distinct and essential psychological facet to Enemy, but the film belongs to Gyllenhaal, who delivers a carefully calibrated and wholly compelling performance. Although technically challenging, the dual roles of Adam and Anthony tempt a facile, Jekyll and Hyde approach. Fortunately, Gyllenhaal and Gullón’s screenplay take a much more nuanced path in their depiction of the duplicates. Adam and Anthony are more akin to ragged-edged complements than perfect mirror images.

Each man's anxieties are expressed to some degree in the other; each is a shadow in the other’s mind. Adam is both attracted to and repulsed by Anthony: his sexual aggression; his talent for deception; his status quo-affirming profession (the “circuses” that Adam decries); the stability and confinement represented by the actor’s marriage and imminent child. Likewise, Adam’s mere presence seems to incite Anthony, as though the professor’s recessive personality, stammering vacillations, and bachelor rootlessness were a personal insult. Adam and Anthony are not yin and yang in equilibrium, but annihilating matter and antimatter. As in the doppelganger legends of old, the simultaneous existence of both suggests a wound in the universe, a glitch that must be corrected. It is as though one man is a projection of the other. Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi’s riddle comes to mind (also paraphrased in Cronenberg’s The Fly): am I the First who dreamed he was the Second or the Second now dreaming he is the First?

Once the twins become aware of one another, Anthony suggests that he and Adam have a face-to-face encounter. The pair arrange to meet in a seedy motel known to Anthony, rendezvousing in a drab room where dull, brass-colored light leaks in through drawn curtains. From across this space, the two men regard each other warily. Adam cowers against the wall, shifting from one foot to the other, while Anthony approaches slowly but purposefully. They peer into each others’ eyes and hold out their hands for comparison, Adam’s trembling slightly. “Maybe we’re brothers,” Anthony offers conversationally, sounding only half-convinced. Adam, visibly frightened, shakes his head with certainty: “We’re not brothers.” When Anthony starts to become insistent and hostile, Adam flees the motel in a state of near-panic.

The meeting between the duplicates sends Adam into a psychological tailspin. Demonic arachnids invade his dreams, and his grasp on his identity becomes increasingly tenuous. Even his own mother (Rosellini) treats him as though he were someone else, confusing essential facts and trivial details of his life. Meanwhile, the meeting with his twin ignites something predatory in Anthony, whose behavior becomes increasingly intimidating and sinister. He even stalks an oblivious Mary on her commute one morning, leering at her with reptilian hunger. The actor later turns up at Adam’s apartment in an agitated state, and begins dictating what can only be described as terms of surrender. The two of them, Anthony explains, will cease all contact and never interfere in one another’s lives again, but not before he subjects Adam to a twisted, humiliating revenge for the man's supposed transgressions.

While the lines that define each man have gradually become smudged, Anthony’s scheme vandalizes those borders utterly. Visual markers that the viewer could formerly rely upon—Adam’s tweed jacket, Anthony’s wedding band—begin to vanish. The story returns to earlier locales and situations, echoing events that have already occurred. Like colliding particles governed by quantum mechanical principles, the duplicates separate and travel on distinct trajectories, but they remain entangled by invisible strands. The film eventually returns (in a fashion) to the sex club and the creeping spider, and the vague disquiet that has haunted Adam’s journey begins to rise to a keening terror.

Much of what unfolds in Enemy’s final scenes has a patina of grim destiny about it, as though the viewer were merely seeing one iteration of an algorithm that will repeat endlessly (like The Tenant’s eternal plunge into a screaming mouth). The entirety of the film becomes a prelude for its final, devastating shot, in which awareness (if not understanding) suddenly descends like a spring-loaded booby trap. That shot presents a sight that is at once shocking, baffling, and swollen with primeval terror. The truth that Adam abruptly confronts—and then accepts with a weary exhale—realigns all that has come before, and yet explains nothing. It simply affirms what the film has intimated in every frame: that the snare has already been laid, the careless step already taken, and the prey’s fate already sealed.