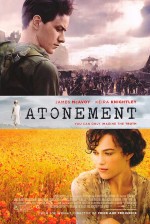

2007 // UK - France // Joe Wright // January 7, 2008 // Theatrical Print

C - There's a powerful film about the dimensions of morality somewhere beneath the surface of Atonement, but director Joe Wright doesn't permit that film to fully emerge. Something tantalizing is going on in this adaptation of Ian McEwan's novel, especially in the film's first act, and thereafter whenever Romola Garai is on screen as the eighteen-year-old incarnation of the film's primary narrator, Briony Tallis. Unfortunately, Wright and screenwriter Christopher Hampton seem content to coast on filmic conventions that, while attractively realized, seem misplaced or outright leaden. It's challenging to discuss Atonement in detail without revealing its twist conclusion. Suffice to say that the daring metatextual themes of the source material seem to lose something in the translation to the screen.

Briony is thirteen years old at the film's 1935 opening, set on her family's beautiful estate in the Surrey Hills of England. Briony's adult sister, Cecilia, and Robert Turner, a son in the household's servant family, have recently returned from school at Cambridge. Briony's cousins are staying at the mansion, and her adult brother Leon arrives with a business associate. The film's first thirty to forty minutes take place during one sweltering summer day, as these characters gather at the Tallis estate and a tragedy unfolds. There is a repressed attraction between Cecilia and Robert, but also a tension born from the peculiar fissures of British class. Briony, who aspires to be a writer, sees and reads things on this fateful day that she doesn't fully grasp. She makes some sensational assumptions, tainted with her own resentments and wishful thinking. Eventually, she accuses Robert of a brutal crime.

Atonement then fast-forwards four years. Robert, serving out a sentence in the Army, is separated from his unit in occupied France. Cecilia, estranged from her family, is waiting for his return in London. Briony is training to be a nurse, a penance for the accusation that has dealt Robert and Cecilia so much hardship. The events of that day years ago have continued to fester, their consequences reverberating across oceans and lives.

Atonement is strongest when it blazes directly into this ethical briar patch, and Wright's skills as a storyteller shine during the first act. The film has a stagy quality in these scenes, but it is remarkably effective at conjuring an atmosphere of Old Testament family doom. Wrightâ's direction is taught and ominous; we sense that something foul is unfolding long before anything unpleasant actually occurs on screen. The film's sound design is memorable and relentless, suffusing parlors and gardens with Faustian menace. Wright replays scenes from different perspectives, and leaps between his characters to suggest their thoughts. It's not an original approach, but it thrillingly serves the film's interest in misunderstandings, intentions, and inhibitions. In short, Atonement adeptly addresses the essential thorniness of human relations. The events that occur at the Tallis estate might be implausible, but not distractingly so. The elements that swirl through the story--sex, gender, class, maturity, culpability, narcissism--are sufficiently intriguing that they produce a wicked, enticing brew.

And then... well, things just sort of meander off into the wilderness. Once the story leaps forward to the British retreat from France, Atonement abruptly turns into a turgid World War II drama. It's not a bad film, mind you, but much less interesting than the film that preceded it. Cecilia and Robert pine for one another. Robert trudges across France. Briony tends to the incoming wounded. These sequences are shot and edited well, but they don't offer anything original and their relationship to the film's established themes is tenuous. There is a remarkable continuous shot, nearly five-minutes long, when Robert arrives at the beaches at Dunkirk. The camera pans and pans and just keeps on panning over a stunning tableau of British forces, calling to mind a Pieter Bruegel painting. From an aesthetic and technical perspective, it's an achievement. What purpose it serves is less clear. Wright has apparently admitted that he was just showing off with this sequence. Why bother, then?

I'm not quite sure how to apportion the blame here. McEwan's novel is widely regarded as a modern masterpiece, and Wright's film is apparently a faithful adaptation. I suspect that Wright is too entranced with the epic sweep of history on display in the source material, and as a result neglected the slighter threads that cohere its scenes. Regardless, it's frustrating to watch a bolder film slip right through Wright's fingertips while he lingers mournfully over the devastation of the French countryside by the Nazis.

The final hour or so of Atonement is rescued primarily by Romola Garai, who gives a strong, tormented performance as Briony. Even when her scenes are aimless, Garai manages to find fascinating stripes in Briony, portraying her as earnest and penitent but a little touched. Keira Knightley and James McAvoy exhibit an urgent, torrid chemistry during the first act as Cecilia and Robert. Neither actor has the presence to lend the rest of film much gravity, however. McAvoy in particular seems to be literally wandering through his scenes, where he is granted only the thinnest and most humdrum characterization. Atonement flares to life a bit in the final confrontation between Briony, Cecelia, and Robert, but Wright has already painted himself into a corner by then.

Eventually, Vanessa Redgrave appears as an elderly Briony decades later, and there are jolting revelations. The floor drops out from under us, and fresh strata of meaning are revealed. Unfortunately, the twist feels more obligatory than earned. I have a strong sense that the conclusion is vastly more effective on the printed page.

Atonement begins as an insightful and sharply executed tragedy, only to lose its way in the mire of functional period drama banality. The lean and nasty first act and Garai's engrossing performance just manage to redeem Wright's extravagant missteps, making for a worthwhile, if frustrating, experience, and a glimpse at what might have been.