Revolutions, Glorious and Otherwise

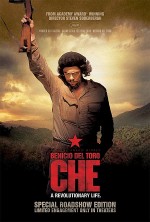

2008 // Spain - France - USA // Steven Soderbergh // January 31, 2009 // Theatrical Print

A - It's unlikely that Steven Soderbergh's meticulous, two-part marathon Che will ever end up a beloved film, to be devoured over and over. It's simply too sprawling, and especially too heedless of the tactful cloak of "mere entertainment" that so many other biopics don. Not to say that Che disregards entertainment, as the four-plus-hour Roadshow Edition is unmistakably fashioned in the image of the 70mm epics of old": a Marxist Lawrence of Arabia complete with overture, intermission, and printed program. Che will be, I think, a work to be studied with deep fascination and awe, a case study in film-making that is both uncompromising and fiercely focused. Whatever Che lacks in humanity or grace, it is an exhaustive, gritty, and intricate cinematic dissertation on revolution as a social, political, and military process. The result is one of Soderbergh's finest films since his debut, sex, lies, and videotape, although Che far surpasses that work in its ambitions.

Over the course of its 250+ minutes, the Roadshow Edition of Che offers two feature-length films. Che: Part One, also known as "The Argentine", depicts Ernersto "Che" Guevara's role in the 1958-59 Cuban Revolution, while Che: Part Two, "The Guerilla" focuses on Che's participation in the failed 1967 Bolivian revolution. It's perhaps misleading to label Che a biopic or even a character study, for as appropriately magnetic as Benecio Del Toro might be in the title role, the film isn't that invested in Guevara's inner life. Consequently, its approach to the man is less psychological than phenomenological, although it sketches Guevara's personality boldly and with a grand attention to consistency. Che eschews the usual tactic of following its protagonist through a personal evolution; Guevara leaves the film much the same as entered it, his values unmoved and his ideals intact. However, neither does Che take a complementary approach: the world around Guevara doesn't change, either, strictly speaking. What Soderbergh delivers isn't so much a story as a two-act study, a compare-and-contrast exercise that offers a slightly melancholy view of history, at once breathless and oddly ambivalent. If Che has a thesis, it's that slight changes in time, place, and luck can make all the difference in a revolution.

Based on that description alone, you likely already have some notion as to whether Che is your cup of tea. On paper, the plot would sound fairly... well, dull. "The Argentine" follows Guevara through the Cuban revolution, from his first meeting with Fidel Castro through the flight of ousted U.S.-backed president Fulgencio Batista. Similarly, "The Guerilla" tracks Guevara from his vanishing from public life through his execution in Bolivia for his attempts to foment armed rebellion there. That's essentially the plot of Che: a successful revolution followed by a failed revolution. Soderbergh's approach is at once rigorously straightforward and sharply organic. Che reflects the director's absorption with the fine details of these two journeys, tracking precisely how Guevara traveled from Point A to Point B and accounting for all the myriad factors that contributed to his fate.

It's an unusual way to make a film—Che's drama is almost incidental to its academic and artistic posture—but both its novelty and its execution are fairly breathtaking. Certainly, Soderbergh's ambition to capture every jot of the process of the Cuban and Bolivian revolutions, at least as Guevara saw them, both explains the film's titanic running time and neatly sidesteps the possible pitfalls of such a scale. For despite Che's length, it rarely, if ever, feels bloated. There aren't any hefty swathes of the film that seem extraneous, which is kind of remarkable given its length. It's an exhausting work of art to take in, to be sure, but it also carries an aura of unexpected discipline. Soderbergh eschews melodramatic dithering for clear statements of political grievance and vast, gorgeous, textured depictions of events. Che occasionally evokes Terrence Malick in its methods, but Soderbergh's film is as scientific as that director's works are poetic. What Che offers is a painstaking characterization of revolution as an essentially circumstance-driven process. For all of Soderbergh's apparent sympathy for leftist values and Marxist ideology, the film emerges as a smooth rejoinder to the aura of inevitability that communist propaganda so often peddles.

A political critique of Che would likely zero in on the film's essentially positive depiction of Guevara, and the oh-so-convenient way its two mega-act structure papers over the Cuban revolution's human rights horrors. To be sure, Che seems to be counting on an audience sympathetic to the notion of military resistance as an essential component of the struggle for political and economic justice. It doesn't so much shed a tear or bat an eye the first time Cuban guerrillas rip into Batista's army with machine guns. (Whether the viewer will believe the communists were unprovoked or not will likely depend on his or her own political tendencies). That said, there is something to be said for the distinction between a positive portrayal and a romantic portrayal. While the former is a prominent component of Che's character, it rarely indulges in the latter. The film establishes balance and credibility not by shoehorning in awkward scenes of character development, but by letting Guevar's temperament emerge delicately from the revolutionary events that surround him. The man is shown to be generous, courageous, honorable, and compassionate, but also callous, bigoted, arrogant, and more than a little bloodthirsty. Che is not a complex portrait—it's not that complex, and not really a portrait—so much as it is silent on the question of the man's ultimate benevolence or malevolence in the broader tapestry of modern history. If nothing else, Che depicts revolution as anything but fun, and dismisses that its outcomes are in any way fated, even in the face of monstrous oppression.